A. Sutherland – AncientPages.com – Deir el-Bahri, a sacred resting place for the pharaohs, is a mountain valley on the western bank of the Nile River, near Thebes, an archaeological site of tombs and temples.

In ancient times, Deir El-Bahri (Bahari), of which name means “Northern Monastery,” was an essential part of Theban’s royal necropolis. It is located on the West Bank of the Nile opposite the famous Karnak is a large rock formation formed by the cliff of the plateau of the Libyan desert.

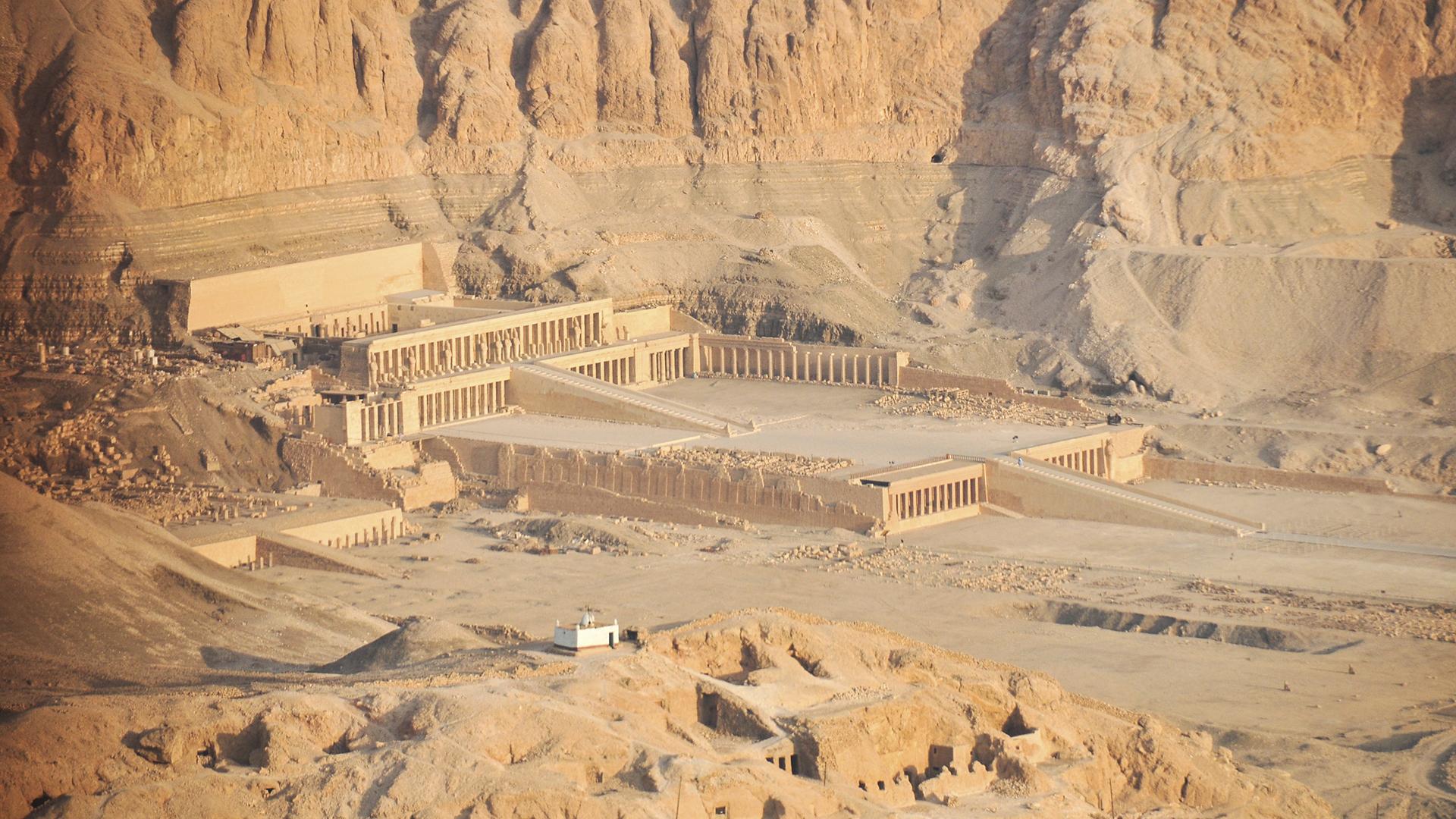

Deir el-Bahari. The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut – aerial view in the early sunlight. Credit: Adobe Stock – WitR

Many prominent royal figures of ancient Egypt found a resting place in the sacred area of Deir el-Bahari.

The area’s perfect geographical location, with a somewhat flat plain landscape that rises gradually westwards from the Nile, before it suddenly ends in a steep rock wall that surrounds the valley in a U-shape. At the bottom of this quiet valley, resting against the mountain wall, are the three most magnificent royal temples side by side: Mentuhotep 2’s tomb and temple from about 1959 BC., Hatshepsut’s the famous mortuary temple was built on three terraces with inclined ramps.

In his work “Egypt’s ancient heritage,” Rodman R. Clayson writes that rows of fine columns around each terrace are arranged in beautifully clear perspective. The columns of most Egyptian temples were in covered halls leading through growing dimness to the ultimate sanctuary.

In Hatshepsut’s temple, the square columns led to spacious courts open to the sky.” 1

The capitals of some of the columns are sculptured to represent the cow goddess Hathor, the goddess who nursed and every king, including their mythological ancestor, the god Horus, in Egypt’s distant past. The goddess Hathor, one of ancient Egypt’s most outstanding female deities had from bygone times a special connection to the area.

Sculptures of pharaohs entering the Funerary Temple of Hatshepsut. Credit: Adobe Stock – unai

Hatshepsut’s temple is beautiful. All credits go to the architect Senenmut, chief of the enthusiastic and dedicated group of Egyptian officials who served the queen Hatshepsut. It is said that the two may have been lovers, but there is no clear evidence to support this claim. However, “Senenmut stood in some special relationship to her.” 1

The temple “resembles no other of its time, although its form was doubtless suggested by the neighboring tomb complex built by Mentuhotep some 600 years earlier. Hatshepsut’s building was not a tomb but a temple in honor of her “divine father,” [the national god Amon-Re]… To Hatshepsut, it was the paradise of Amon, and on its approaches, she planted the myrrh and incense trees which she had brought from Punt in far Somaliland.”

Colorful murals depicting the expedition, which Hatshepsut sent to the land of Punt, are also stunning.

Beside her temple complex are the ruins of what was once the monumental Temple of Mentuhotep III. Many of Egypt’s great Pharaohs, such as Thutmose III and Rameses II, celebrated their campaign victories by building magnificent temples decorated with sculptures and paintings of outstanding beauty.

Another structure is the tomb temple of Hatshepsut’s successor Thutmosis III, but landslides destroyed the temple in ancient times.

Nevertheless, many architecture experts and ordinary people consider Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple the most beautiful temple in Egypt.

Just east of the hot, dry, and silent Deir- el-Bahri on the other side of the Nile, there is the famous Karnak Temple – by far considered the largest temple complex of antiquity, dedicated to the god Amon-Ra, whose name was with time associated with several other gods.

Credit: Adobe Stock – Stockbym

Deir- el-Bahri also has a prominent neighborhood of the Valley of the Kings, the place where the kings of the new kingdom (around 1550-1069BC) dug out their rock tombs.

Another tomb is that of Pharaoh Amenhotep I, who was deified after his death (c. 1494 BC) and became the patron saint of this part of the famous necropolis. The grave of his wife Merit-Amon was found nearby in 1929, but his tomb remains undiscovered.

The original location of Amenhotep’s tomb has not been securely identified. A report on the security of royal tombs in the Theban Necropolis commissioned during the troubled reign of Ramesses IX informs that the tomb was then intact.

However, its location was not never clearly specified.

Two possible sites for Amenhotep I’s tomb have been proposed, one (KV 39), located high up in the Valley of the Kings, and the other at Dra’ Abu el-Naga’, Tomb ANB. Excavations at KV 39 suggest it was used (or reused) to store the Deir el-Bahri Cache, which included the king’s well-preserved mummy, before its final reburial. The tomb ANB is a strongly suggested candidate because it contains objects bearing his name and the names of some family members. Sometime during the 20th or 21st Dynasty, Amenhotep’s original tomb was either robbed or considered insecure and emptied, and his body was moved for safety, probably even several times.

It was finally located in the Deir el-Bahri Cache, hidden with the mummies of numerous New Kingdom kings and nobles in or after the late 22nd dynasty above the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut.